Education is not just about what and how we learn. It's also about how we perceive ourselves and our place in the world. More to the point, it’s about how we view children and their place in the world. Children's innate learning skills were once a given, and learning was a joy and not laborious, boring, and counterproductive. We've gotten away from that model, but we can reclaim it. Here we'll summarize where we've been so that we can better understand the dynamics we must unravel to once again honor and take advantage of the way our brains are designed to learn.

Before civilization, there was no such thing as school. With the few and diminishing primitive tribes that survived until the modern era, we have had the opportunity to make some fascinating insights into these school-less societies.

Before civilization, there was no such thing as school. With the few and diminishing primitive tribes that survived until the modern era, we have had the opportunity to make some fascinating insights into these school-less societies.

|

There are currently about 100 “uncontacted tribes” in the world (source), mostly in Papua New Guinea and the Amazonian countries. Not one of them has a school. Yet one could approach a 12-year-old child in any of these tribes and they would have a profound and detailed knowledge of the environment that surrounds them, their customs, oral histories, and know hundreds of stories and songs by heart. Yet, there is little if any observable “instruction’ or “teaching," at least in the form we would recognize. For example, nobody drags a kid around in the Amazonian rain forest, takes them tree to tree, tells them the names, and expects them to memorize it for the future. The same random 12-year-old would have a knowledge beyond that of a professional Ph.D. naturalist with decades in the field. HOW DID THEY LEARN SO MUCH?

|

Education in primitive societies focused on acculturation. Methods were quite varied, but they generally saw children as autonomous and naturally curious learners. They acquired knowledge through song, storytelling, and active participation in tribal life (source). This active learning inspired their curiosity and increased their ability to remember things because it was experiential rather than primarily intellectual.

Naturalist Jon Young refers to the learning process that indigenous children went through as “coyote teaching.” The coyote is seen by many indigenous people in the Americas as the trickster. Young posits that native cultures “tricked” children into learning without the kids even realizing they were being taught, and it works amazingly well. Remember the earlier example of the young kid who knew more than the scientist who studied and worked on the same subject matter for decades.

In fact, adults in these primitive cultures gave children the autonomy to play, learn and explore on their own. They understood that such activities are a child’s most natural way of learning.

Fast forward to the dominance of agricultural societies, the settling down of people into what we now think of as early civilizations, and later into complex civilizations such as medieval Europe or pre-colonial Asia. With stricter societal hierarchies (religions, armies, kingdoms and commercial structures), people began to see children not so much as willing, curious learners but instead as ignorant, empty vessels who would resist learning unless they were forced into it. Children were also treated as property without any real rights to speak of. (source)

The push for universal education can be traced to the Reformation. Martin Luther thought that each person needed to read the Scriptures to achieve salvation. Thus, people needed to know how to read. The progenitors of the Reformation saw universal public education as Christian duty. (source)

The American experiment with public education began in New England around 1690 and was structured to promote religious goals (source) and obedience.

|

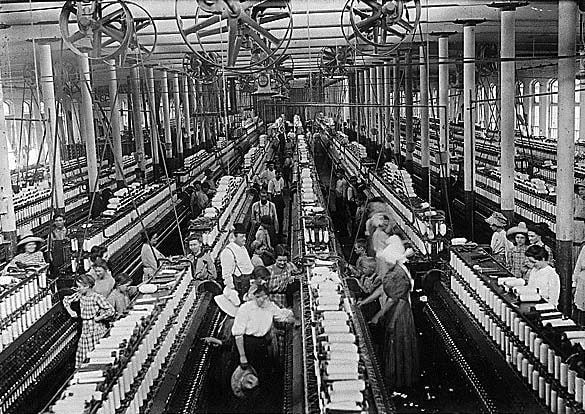

The industrial revolution entrenched the idea of coercing and molding children even more but shifted the priorities a bit. Industry relied on people being punctual, able to follow strict rules, and endure boring, repetitive tasks day after day. Inspiring kids with fun and engaging learning opportunities was not seen as necessary; in fact, it was counterproductive. One could argue that the more tedious and boring school was the more prepared people would be when they entered the workforce. On a national level, the system worked to promote unquestioning patriotism and a pool of future soldiers and police who would follow orders without question.

|

Many scholars and authors have referred to the public education system that came out of the industrial revolution as the "factory model of education" due to its top-down management, standardization, age-based classrooms, and focus on efficiency and measurable results. Others see this analysis as overly-simplistic, referencing a much more complex and nuanced development of the current public school model. At the Center for Inspired Learning, we call it the Whole Classroom Instructional Model, or WCIM.

|

We can allow historians to debate the finer points of how we got here and to what extent schools do or do not resemble factories. The point is that public education in the United States is largely based on the view that children should learn in classrooms with tens of other kids of varying mastery levels, interests, and learning styles, receive a similar curriculum, and take standardized tests that have nothing to do with the world they will enter in adulthood. We allow very little space for children to be curious learners, let alone give them any meaningful level of autonomy to learn the way their brains were designed which is through innate interests and the experience of doing things. This is why so much of what is learned in school is quickly forgotten and also why boredom is rampant in the classroom. (source)

|

There has been widespread criticism of the Whole Classroom Instructional Model from the beginning. Alternative education pioneers like Maria Montessori (1870-1952) and Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) understood the inherent contradictions and founded education models that valued the whole child. Education reforms in the United States to address the issues with WCIM have tended to chip away at the margins rather than recognize the system as obsolete, harmful, and needing replacement. A 1983 publication of the US government, A Nation At Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform, famously stated, "If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war. As it stands, we have allowed this to happen to ourselves." The following 40 years would see a cascade of reforms and money thrown at public education to solve the problems, but the results have been underwhelming at best.

The history of public education needs a radical course change. It’s time to apply what we know about how kids acquire skills and knowledge. The Center for Inspired Learning is dedicated to revolutionizing public education system by replacing outdated and harmful practices with ones that teach children through participation, inspiration, and curiosity (source).

"Education is what remains after one has forgotten what one has learned in school. It is a miracle that curiosity survives formal education."

— Albert Einstein

KEY TERMS

Whole Classroom Instructional Model (WCIM) - The century-old structure of sorting children by age, randomly placing them in groups of 20 to 30, then teaching them the SAME material, at the SAME time, at the SAME pace, in the SAME way, by the SAME teacher. Children are seen as passive recipients of information and knowledge and rarely, if ever, take ownership of their learning. Students move between classrooms during the day, move “up” through grade levels over the years, and eventually leave school for the workforce, likely to never step foot again in the place where they spent so much of their childhood. Assessments in this rigid system are done primarily via test-taking. The teacher is at the center of the learning process.

Synonyms:

Learner-Centered Model (LCM) - The impetus for learning comes from a child's innate curiosity. This structure gives students control over the content of lessons and the learning method and promotes autonomy and active learning. The learner is at the center of the learning process. The teacher is seen as a facilitator of the learning process rather than "the sage on the stage."

Synonyms:

Inspired Learner Model (ILM) - A learner-centered education model developed by the Center for Inspired Learning that is designed to work in US public elementary schools using existing school infrastructure, budgets, and staffing. Its components include project and activity-based learning (PABL), peer mentoring, enhanced learning through technology, student choice, parental involvement, community engagement, and other mechanisms to support and encourage children to become lifelong curious learners. Besides traditional elementary school curriculum, ILM may include an emphasis on self-care, financial literacy, media and digital literacy, communication skills, conflict resolution, global citizenship, the arts, and learning at least one foreign language.

Synonyms:

- Standardized Education

- Teacher-Centered Learning

- One-Size-Fits-All Instructional Model

- Factory (Assembly Line) Education Model

- Taylorist Model

- Coercive Schooling

Learner-Centered Model (LCM) - The impetus for learning comes from a child's innate curiosity. This structure gives students control over the content of lessons and the learning method and promotes autonomy and active learning. The learner is at the center of the learning process. The teacher is seen as a facilitator of the learning process rather than "the sage on the stage."

Synonyms:

- Individualized Learning

- Student-Centered Learning

- Adaptive Learning

- Blended Learning

- Personalized Learning

- Competency-Based Education

Inspired Learner Model (ILM) - A learner-centered education model developed by the Center for Inspired Learning that is designed to work in US public elementary schools using existing school infrastructure, budgets, and staffing. Its components include project and activity-based learning (PABL), peer mentoring, enhanced learning through technology, student choice, parental involvement, community engagement, and other mechanisms to support and encourage children to become lifelong curious learners. Besides traditional elementary school curriculum, ILM may include an emphasis on self-care, financial literacy, media and digital literacy, communication skills, conflict resolution, global citizenship, the arts, and learning at least one foreign language.

A 501(c)(3) Nonprofit - EIN 82-4387189